| This is the web site of author Steven Saylor. Click here to visit the Home Page. |

|

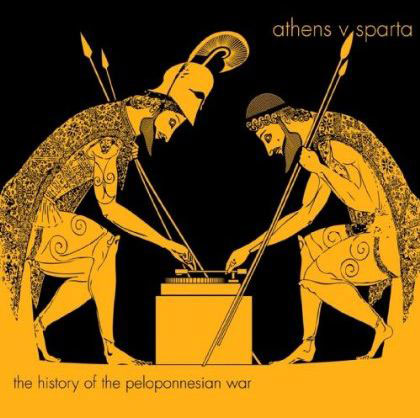

Athens v. Sparta: On October 24, 2010, Steven was honored to deliver a brief introduction to a live performance of Athens v. Sparta at the Hyde Park Theater in Austin, Texas. AvS combines readings from Thuycidides’ History of the Peloponnesian War with a suite of original rock songs. The combination of grim narration, ethereal music, and trenchant lyrics is spellbinding. The official AvS site is here, and you can hear the whole album and watch a video here. You can also hear samples and download from Amazon or from

I’ve been asked to give the introduction because I, too, have been known to take some poetic license with ancient history. My field of expertise is ancient Rome, and I don’t claim to be an expert on Greek history, or the historian Thucydides, or the events of the Peloponnesian War, that great war between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies. As I say, my field is ancient Rome, but you cannot immerse yourself in Rome without getting some Greece on you—and because I write historical fiction, I spend a lot of time thinking about ways to bring ancient characters to life and to make stories from ancient history exciting and moving and emotionally gripping for a modern audience. So I do feel I am among colleagues up on this stage, because what Charlie Roadman and the others involved in Athens v. Sparta have done is to create a kind of historical fiction, drawing on the ancient source of Thucydides and remaining true to his sprit even while casting his words into a completely modern idiom, a suite of rock songs. There are many famous historians form the ancient world—Livy, Tacitus, Polybius, Plutarch, and on and on. You can spend a lifetime reading and studying them. Of all those historians, probably the one whose work is best known to any reasonably educated person is…not Thucydides…but Suetonius, who wrote biographies of the first twelve Caesars, and thus provided material for everything from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar to the novel and television series I, Claudius. Suetonius is certainly the historian I’ve been spending the most time with lately, poring over lurid stories about Tiberius and his geriatric sex-pad on the island of Capri, and Caligula making his horse a senator, and Nero fiddling while Rome burned. Suetonius is full of sex, murder, scandal, family drama, astrology, dreams, omens, and portents—and just maybe, a little history. And that’s why we still read him today. But among the ancient historians, there is another, very different example of how to write history, and that is Thucydides. Thucydides does not give us scandal and gossip and sexual intrigue, though he probably could have. Instead, Thucydides gives us the hard, cold facts of politics. He describes the maneuvers made by men as they follow the seemingly inevitable path to war, and he recites the justifications they make for the terrible atrocities that take place during wartime. Thucydides takes history very seriously, and the result is one of the most chilling books ever written.

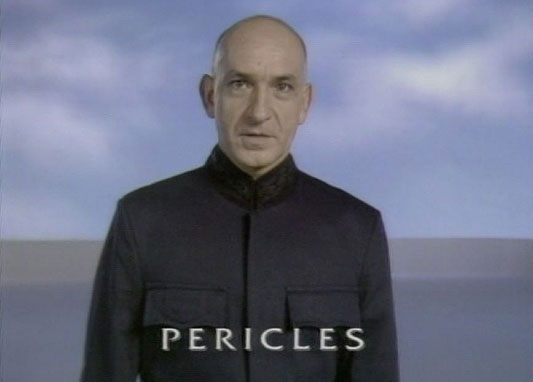

What was the Peloponnesian war? 2500 years ago, war broke out in the Eastern Mediterranean between two powerful states, Athens and Sparta. It convulsed the region, and destroyed an empire. At the outset of war, Greece was made up of precarious alliances of self-ruling city-states. They had come together only once, to repel the attack by the Persian Empire some 50 years earlier—reference, if you must, the movie 300—but that wartime alliance did not last, and soon two power blocks confronted each other: the states following Athens, the inventor of democracy and the supreme sea power, and those in the Peloponnesian League allied to Sparta, the greatest power on land. The war lasted for 27 years. Who lost? You will hear about that tonight. Much of what we know about that war comes from the writings of one man. Thucydides has been called the world’s first war reporter and the originator of objective history. His insights into the behavior of men under extreme pressure and the decisions that can lead to war still speak to us urgently today. What do we know about Thucydides? We know that he was an Athenian, and that he was born somewhere around 460 B.C.; so, when the war broke out in 431 B.C., he was about 30 years old. We know that he owned gold mines in Thrace, the most northerly region under Athens’ influence, and so, because of his knowledge of the area and his connections there, the Athenians sent him as a general to an island called Thasos off the coast of Thrace. In the year 424 B.C., seven years into the war, a Spartan general attacked the Thracian city of Amphipolis. Thucydides was summoned to held defend Amphipolis, but he arrived too late to prevent a Spartan victory. The people of Athens, angry at Thucydides for the loss, voted to exile him. And so Thucydides sat out the rest of the war, and apparently was free to travel among the enemies of Athens, perhaps to interview in person many of the movers and shakers, perhaps even hearing firsthand some of the speeches and debates he records in his history. He used this time of exile and freedom of movement to gain insight into both sides in the conflict. The result was his account of the causes and the conduct of the war, a book which he tells us was not written for the moment, but to be “a possession for all time.” Because, as Thucydides tells, us, “human nature being what it is, such events will almost certainly repeat in the future.” How right he was. Thumb though a copy of Thucydides, and on almost every page you can find words that echo today. On the build-up to war: “Negotiations ended more and more in impasse, and ultimatums grew more frequent and more insistent. Men ceased to use the word ‘whether,’ and instead talked more and more in terms of how and when.” Pericles, the elected leader of Athens, talking about politics in the city: “We do not say a man who takes no interest in politics is a man who minds his own business; we say that he has no business here at all.” The Spartan general Archidamas, trying to dampen the war-fever among his colleagues: “In the course of my life I have taken part in many wars, so you must forgive me if I do not share the general enthusiasm, or think that war is necessarily a good or safe thing: We must not delude ourselves with hopes of a short campaign. I fear that we will not end what we begin, and will bequeath to our children many problems and much suffering that will take a long time to heal.” A Spartan general to the people of Acanthus, whom the Spartan wished to “liberate” from Athenian control: “The Spartans have sent me to uphold our pledge to liberate Greece. I am thus distressed to find that you have shut your gates against me. For I thought that we were coming to allies who wanted us….Others will think that it is very strange that you have failed to welcome me. They will think there is something unreal about the liberation which I offer. I assure you I have not come her to do you harm , or to take sides in your internal affairs. If you still say that we should not force liberty on anyone against their will, then I shall call upon the gods to witness that I came here to help you but I could not make you understand, and I shall try to bring you over by force and to lay waste your land. Please understand that we Spartans have no imperial ambitions. We are only justified in liberating people against their own will because we are acting for the general good.” Again, Pericles of Athens, on using the words right and wrong in war time: “The grounds of any war are usually ambiguous, so you should be wary of using supposed moral sanctions too glibly….Like all forms of government , our democracy is as liable to the same taints as any other, for we too, unless we are rigorous, may become confused by feeling that because our form of government is right, anything we do will inevitably be right also. So I would ask you to spend the emotive currency of our vocabulary [talk of right v. wrong] sparingly, and to try not to debase it by overuse.” Again, Pericles (after the disenchanted Athenians began to blame him for persuading them to go to war in the first place): “I knew it would be easier to persuade you to go to war than to maintain your spirits year after year. I know too well that public confidence is volatile among us….We are threatened with the loss of our empire through the hatred we have incurred in administering it. But it is not longer possible for us to give it up…To those who say that it was wrong to take it [our empire] in the first place, I reply that it would be more wrong and dangerous now to let it go. The right policy is what it always was: to endure patiently whatever the gods have in store for us, to face calamity with an unclouded mind, and to meet our enemies with courage. This was the old Athenian way, and you are still Athenians.” (Of course, Pericles lived only that years into the war, and did not see the following 25 years of bloodshed and catastrophe that he had helped to bring about.) And finally, Thucydides on human nature: “Men speak and even behave nobly and sensibly when they are not threatened, but when war interrupts the economic benefits which peace provides so conveniently, it inevitably changes their character. Words change their meanings. Recklessness is renamed courage, sensible caution is called cowardice, moderation is a form of weakness, and as for being able to see all sides of a complex question, it is damned as incapacity for action. Words such as revenge, punishment, deterrence and justice are confused and become interchangeable. Brutality becomes a virtue. Callous killing is thought to be moral. And revenge is even more admirable than self-preservation.” *** I first read Thucydides about 35 years ago, when I studied history and Classics at the University of Texas here in Austin. Even then, Thucydides’ clinical examination of human nature sent a shiver down my spine. I next thought seriously about Thucydides in 1991, when the first Bush was president, and Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. On the very eve of the Gulf War, BBC Television broadcast a program that was also shown here in the States on PBS. It was called The War That Never Ends. The show opened and closed with images of Saddam Hussein, the debates in the UN, and the American preparations for war, but in between, on a bare stage, wearing simple costumes, various actors recited dialogues and debates from the history of Thucydides. Perhaps the most memorable was Ben Kingsley as Pericles. The effect of seeing those actors recite the words of Thucydides was absolutely chilling, and truly unforgettable—a timeless look at the circumstances and arguments that seem to lead inevitably to war, over and over again. To my knowledge, The War That Never Ends has never been available on VHS or DVD, but some day we may all be lucky enough to see it again.

And then I found about tonight’s presentation, Athens v. Sparta. How did I find out about it? On facebook, of course. A facebook friend, a Classicist visiting Austin, posted a rave review of something called Athens v. Sparta. What on earth could this be? I followed the links to reverbnation.com, and there I saw the song list. Here were purported rock songs with titles like “The Melian Dialogue,” “Peace of Nicias,” “Arichidamian War,” and my personal favorite, that tongue-twister, “Aegospotami.” Well, I thought, this has got to be a Classicist’s wet dream. And sure enough, as I listened to the songs online, I was again affected as I was when I was an undergraduate encountering Thucydides for the first time, and again when I watched The War That Never Ends in 1991. The words are, as always, chilling; and the music seemed to me a perfect match — pensive, plangent, brooding, moving yet somehow detached — like the writing of Thucydides himself. However, I have yet to see the show performed live. So, tonight, along with you, I am very excited to be here for this performance of Athens v. Sparta.

Text copyright © 2010 by Steven Saylor |