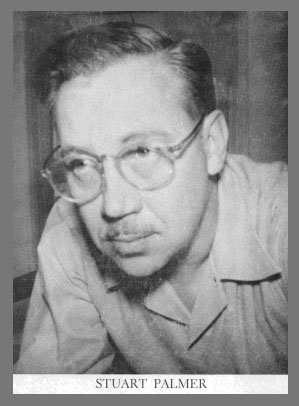

STUART PALMER & HILDEGARDE WITHERS An Appreciation by Steven Saylor  It is a curious thing, how quickly and completely a writer of considerable renown can vanish from the scene. A case in point: the mystery writer Stuart Palmer. Palmer was once routinely mentioned as one of the best authors in the genre, and his intrepid heroine of fourteen novels and dozens of short stories, a spinster school teacher named Hildegarde Withers, was once ranked among the immortal sleuths of fiction. John Dickson Carr, in his introduction to the 1952 anthology Maiden Murders, wrote: “Here are the old craftsmen, the serpents, the great masters of the game: Mr. Ellery Queen, Mr. Stuart Palmer, M. Georges Simenon.” That old serpent Ellery Queen himself, Fred Dannay, spoke of Palmer in the same breath with Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. And the dean of mystery critics, Anthony Boucher, in The Case of the Seven of Calvary (1937), cited Palmer as a top exponent of the puzzle story along with Erle Stanley Gardner and John Dickson Carr. In 1954 his fellow authors elected him president of the Mystery Writers of America. As for Miss Hildegarde Withers, Boucher named her “one of the first and still one of the best spinster sleuths,” (Four and Twenty Bloodhounds, 1950), and as recently as 1987, in their introduction to Uncollected Crimes, Bill Pronzini and Martin Greenberg could confidently pronounce: “Ask any knowledgeable mystery reader to name the quintessential little old lady sleuth, and the response will invariably be either Agatha Christie’s Miss Jane Marple or Stuart Palmer’s Hildegarde Withers.” And yet, at a recent gathering of well-read, dyed-in-the-wool mystery fans where I delivered a talk about Palmer, when I asked for a show of hands from those who knew his work, or at least had heard of him, hardly a hand went up. Who was Stuart Palmer? We know that he was born in Baraboo, Wisconsin in 1905, was educated at the Chicago Art Institute and the University of Wisconsin, and variously worked (by his own account) as a “supercargo, iceman, publicity writer, newspaper reporter, advertising copy-writer, apple-picker, literary ghost, poet, editor, special interviewer, Hollywood script-writer, etc.” Physically, he was a big man, standing a bit over six feet, two inches tall. In private life, he was definitely a ladies’ man; Palmer’s first marriage was at age 23 in 1928, his fifth and last at age 61, two years before his death in 1968. Palmer’s first novel, not a mystery but set among criminals, was a curiosity called Ace of Jades (1931). The book’s heroine is a wise-cracking gangster’s moll and the tone is meant to be charming, but for this reader the humor is too dated and the storytelling too flimsy to come off. Frankly, I couldn’t get through it.

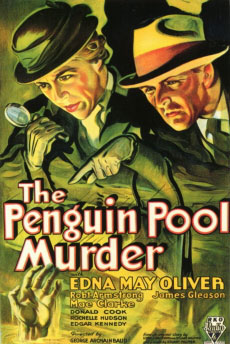

But apparently the legendary publisher Powell Brentano did, and saw in Palmer the makings of a mystery writer. This is how (in a letter to Fred Dannay, probably written around 1949) Palmer recounted the genesis of his second novel, The Penguin Pool Murder (1931), and the creation of the sleuth who would be with him for decades to come: The origins of Miss Withers are nebulous. When I started Penguin Pool Murder (to be laid in the New York Aquarium as suggested by Powell Brentano then head of Brentano’s Publishers) I worked without an outline, and without much plan. But I decided to ring in a spinster schoolma’am as a minor character, for comedy relief. Believe it or not, I found her taking over. She had more meat on her bones than the cardboard characters who were supposed to carry the story. Finally almost in spite of myself and certainly in spite of Mr. Brentano, I threw the story into her lap. She was based to some extent on Fern Hackett, an English teacher in Baraboo High School who made my life miserable for two years. Once I came to get her permission to transfer to another class and she said okay, only she’d be lonesome and bored without our arguments; that I was the only student in the class whom she thought enough of to bother with. I think she started me as a writer. Fern was a horse-faced old girl, preposterously old-fashioned, fine old New England family run to seed, hipped on Thoreau and Emerson. Thus was born Miss Hildegarde Withers, who makes her first appearance in The Penguin Pool Murder escorting some of her elementary school students on a field trip to the New York Aquarium. When a dead body appears in the penguin tank, Hildegarde’s career as an amateur sleuth is off and running, with frequent assistance from Oscar Piper, a gruff police detective as stubborn as she is. (When they first meet and Piper asks who she is, Hildegarde archly replies, “I’m a school teacher, and I might have done wonders with you if I’d caught you early enough!”) At the end of The Penguin Pool Murder, in a peculiar burst of passion, the two run off to get married, but in the sequel, Murder on Wheels (1933), we discover that they came to their senses before they went through with it; Palmer no doubt realized that domesticity would kill their chemistry. In the novels that follow, including Murder on the Blackboard, Hildegarde and Oscar develop an engaging, endearing cat-and-dog relationship.

The Penguin Pool Murder was made into a film in 1932, starring two redoubtable character actors, Edna May Oliver as Hildegarde and James Gleason as Oscar. Oliver’s portrayal was so vivid that it influenced Palmer’s own conception of Hildegarde. From the same letter to Dannay: Then of course when Edna May Oliver played in the first picture (she did three) I fell in love with her, she was so much Miss Withers. I slanted the character even more in her direction, so that the line between life and art became very vague. In her last years Edna played the part of Miss Withers, wore the funny hats and carried the same umbrella she used in the pictures. I wish she’d run up against a murder, but she didn’t....Nowadays I find myself limited in writing about Miss Withers to the scenes that Edna could and would play, and when I write a line of dialogue I hear her crisp Bostonian voice delivering them and milking them dry for every bit of comedy and punch. More novels about Hildegarde, and more movie versions, followed. Palmer himself moved to Hollywood and collaborated on scripts for classic sleuths like Bulldog Drummond, the Falcon, and the Lone Wolf. Off the lot, he played polo with Spencer Tracy and Darryl Zanuck. During World War Two he served as liaison chief for official U.S. Army film making. But he always went back to Miss Withers, working on new novels and short stories right up to his death. And he never forgot his initial success with The Penguin Pool Murder; drawings of penguins, on his letterhead and beside his signature, became his lifelong personal trademark, and in a 1950 humor piece for Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine called “Some of My Best Friends,” he supplied thumbnail sketches of famous fictional detectives from Dupin to Charlie Chan, all in the guise of...penguins. Sometimes Palmer managed to inform the world of Hildegarde Withers with his insider’s view of the movie business. In The Puzzle of the Happy Hooligan (1941), Miss Withers goes to Hollywood to serve as technical advisor on a movie biography of Lizzie Borden. In Cold Poison (1954), she becomes involved in a murder at an animation studio where the trademark cartoon character is named Peter Penguin. In 1957, after Palmer appeared on Groucho Marx’s television show “You Bet Your Life,” Groucho then appeared (along with Miss Withers) in a Palmer short story also titled (though with a more literal meaning) “You Bet Your Life.”

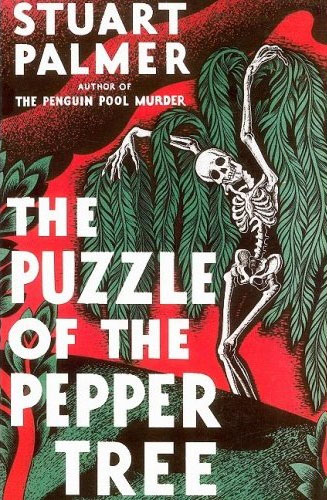

This kind of playful nudging and cross-referencing runs throughout the Withers series, which takes the New York spinster sleuth as far afield as Catalina Island (The Puzzle of the Pepper Tree, 1933), foggy England (The Puzzle of the Silver Persian, 1934), and Mexico City (The Puzzle of the Blue Banderilla, 1937). While Palmer had a long-running career in Hollywood, Miss Wither, alas, did not. After making three features as Withers, Edna May Oliver left RKO just as the studio decided to commit itself to the series. The actresses who followed as Hildegarde, Helen Broderick and Zasu Pitts, were dolefully miscast, and the scripts deteriorated; after three more features, the series ground to a halt. Agnes Moorehead, who might have made a marvelous Hildegarde, was approached to play the role in television series in the 1950s, but the project never materialized. In 1972 a TV pilot called A Very Missing Person starred Eve Arden as the spinster sleuth. One of Palmer’s most important relationships, both professionally and personally, was with his friend and sometimes-collaborator Craig Rice, another once-celebrated, now largely forgotten mystery writer (so forgotten, in fact, that it may be necessary to remind readers that Craig Rice was female, despite her first name). Rice’s sleuth was the hard-living, hard-drinking John J. Malone, whose vices were shared by his creator. When Rice fell into a personal and creative slump in the 1950s, Palmer came up with the idea to do a series of stories teaming Hildegarde and Malone, on which the two authors would ostensibly collaborate. In fact, Palmer ended up doing most of the writing, though he and Rice shared equal credit.

In a series of letters to Dannay, who bought the stories for Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Palmer’s comments about the ongoing “collaboration” provide sad glimpses of Rice’s deterioration and of Palmer’s patience, loyalty, and perennial good humor in dealing with her: I have almost finished the Malone-Withers yarn. Having done most of it alone (Craig took my outline and did the first 8 pages very rough) I have thrown most of it to Malone out of gallantry or something....I tried to see Craig when in Los Angeles Monday, and talked to her mother. She is some better, but under a psychiatrist’s care in some nursing home. * * * Here is “Rift in the Loot,” the Withers-Malone story I told you about. Craig was so anxious to get into the act that I let her make some suggestions on the ending, but couldn’t use more than a slight percentage. She is no better, I am sorry to say. * * * What of Craig?...she seems to have dropped out of sight. Last I heard she was engaged to a millionaire from Lichtenstein and needed a quick fifty which I didn’t have. * * * Spent three hours with Craig, and wrote you a long letter about it last night which I have torn up. I am much distressed, as the situation is very much worse than you or I or anyone imagined. * * * Glad you feel the same way about Craig as I do. When she is herself she is a charming, brilliant, talented woman. I don’t intend to be a fair-weathered friend...I should have included an outline of the story, but did not since it would have been 99 per cent Palmer and I wanted Craig, for her own sake, to have a hand in it. * * * Wrote Craig and asked her if she felt up to reading it [“Cherchez La Frame”] and adding dialogue or anything, but haven’t heard from her and imagine she is off to Chihuahua with or without Mr. Bishop, who has a police record as long as your arm—and my arm too. Maybe someday the old girl will get back in the groove again but it won’t be in the immediate future, I’m afraid. Finally, this curious passage, from a letter to a mutual friend: Craig Rice is necessarily on the wagon, and will spend the rest of her life in a wheel-chair, and has finished a novel. She expects to break out of the hospital soon; her children are going to find her an apartment. I have not been down to see her in spite of many invites; the prospect of trying to cheer up an old lady with white hair and no teeth is not inviting. She lives for her New York lawsuit, with high hopes of getting it made—I don’t know if [this] was the accident where she fell down an elevator shaft into the basement of St. Nicholas’ Arena and then was bitten on the situpon by the watchman’s dog, or not. Something along those lines. She wants to borrow money so that her daughter Iris can fly back to testify; what Iris could know about it all is beyond me, and so is the quick fifty.

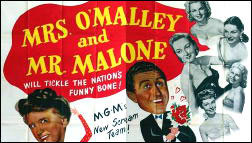

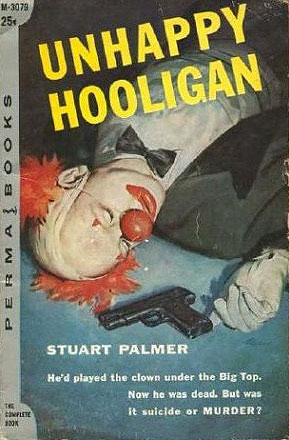

Craig Rice died in 1957. (For more about her, see Jeffrey Marks’ excellent biography, Who Was That Lady?) A collection of the Palmer-Rice short story “collaborations” was published in 1963 as People Vs. Withers and Malone. Early on, two of the stories were bought by MGM and made into the film Mrs. O’Malley and Mr. Malone (1950), with James Whitmore cast as Malone. Hildegarde was unceremoniously dropped, however, and replaced by the very different title character, played by, of all people, Marjorie Main. Much to his chagrin, Palmer saw his beloved Hildegarde Withers transformed by Hollywood into...Ma Kettle! Like his friend Craig Rice, Palmer’s creative powers declined in his later years, though not so precipitously. He continued to write new Withers short stories, some of them as good as ever. His attempt to break away from Hildegarde and create a new sleuth, newspaperman-turned-PI Howard Rook, resulted in one fairly good novel, Unhappy Hooligan (1956), which drew on Palmer’s lifelong fascination with the circus. (His native Baraboo was famous as the birthplace of Ringling Brothers Circus). Twelve years passed before the appearance of the disappointing sequel, Rook Takes Knight, in 1968, which was also the year of Stuart Palmer’s death.

Just as Palmer had stepped in to ghostwrite for his ailing friend Craig Rice, so Palmer’s final, posthumous work was actually completed by another writer, though with less satisfactory results. Using Stuart’s outline and unfinished manuscript, Fletcher Flora received co-author credit for Hildegarde Withers Makes the Scene (1969), which jarringly places Hildegarde among California hippies. Regrettably, Flora infused the novel with a mean-spirited edge very unlike Stuart Palmer. Today, many of Palmer’s books remain long out of print. Bantam brought back a few titles in paperback in the 1980s with handsome deco-inspired covers, and more recently some of the short stories and books have been reprinted by smaller, independent publishers including International Polygonics, Crippen & Landru, and Rue Morgue Press. But, except to the discerning cognoscenti, the author once ranked with Simenon and Queen is largely forgotten, much of his work is hard to find, and his sleuth is best remembered, when remembered at all, by her screen incarnation. (The Hildegarde Withers films still show up on Turner Movie Classics).

Palmer’s critical stature is equally murky. The only thing approaching a serious critique that I have been able to find is a brief essay written in 1985 by H.R.F. Keating as an introduction to Palmer’s Cold Poison (reprinted under its British title Exit Laughing in a series called, appropriately, “The Disappearing Detectives.”) Keating cannot seem to muster much enthusiasm: Odd to reflect that of the dozen fictional detectives I have attempted in this series to prevent disappearing entirely from readers’ view Stuart Palmer’s Hildegarde Withers, Hildy, is...by and large the one least deserving of it.... She was...picked out in 1983 as one of some 90 ‘People of Crime’ in an encycolpædia I edited called Whodunit. Yet really in many ways she does not deserve quite this pre-eminence. Hildegarde Wither is, frankly, no more than a cartoon figure.... Conceived originally as a schoolmarm sleuth from a tough New York school, she was equipped with a rag-bag clutch of possibly useful characteristics: her apricot poodle Tallyrand, a series of outrageous hats, a love for fish-tanks and their denizens.... But she was never allowed more depth than a penny piece. And yet, I would argue that the early novels in the Withers series have an immense if quaint charm, which comes largely from their setting, Manhattan in the early years of the Great Depression, with a flavor as unique and delectable in its own cozy way as the British country manors and villages of Christie or Sayers or Ngaio Marsh. Incidental details of American social history, together with Palmer’s sense of humor, make these books a treasure. And from the outset Palmer understood the sheer enjoyment to be derived from dependable, likable (if irascible) characters who share an offbeat but endearing relationship and exhibit predictable traits and habits. You know you’re hooked on these novels when, at the first mention that Hildy and Oscar are setting out for their traditional spaghetti dinner, you feel like you’re sinking into an easy chair. I would also argue that some of Palmer’s later, more mature novels display the power of a master craftsman, and that their expert plotting and pacing make them models of the puzzle school of writing. Two, especially, have had a powerful impact on my own work.

The highly atmospheric Miss Withers Regrets (1947) is set in an upscale Long Island suburb after the war. For this reader, at least, Palmer pulls off a dangerous but enviable trick: toward the end of the book, you think you see the solution coming, and it’s perfectly logical, and you feel satisfied, more or less, but just a tiny bit let down, since you managed to figure it out, after all—and then, voilà! Palmer springs the real solution on you. This diversionary tactic—the subtle emotional trick of intentionally (though temporarily) disappointing the reader—is very daring, I think. I have done my best to emulate it myself. In Nipped In The Bud (1951), the murder is discovered in the first few pages. You see all the details with your eyes wide open—and yet, there’s a nagging sense (which becomes stronger and stronger as the novel progresses) that something, some detail or other, must have been left out of these opening pages—but what? I remember going back to reread the beginning several times as I was approaching the end, and, right up to the last, not being able to put my finger on it. To be made aware of a puzzle, even to the point of being able to see exactly where the missing piece is located in the book, and yet still being unable to figure out the shape of that piece—for me, that was a glorious and rarefied experience. If I can ever give such an experience to a reader of one of my novels, I will feel quite privileged to have entered the esteemed company of Stuart Palmer, whose influence perseveres, no matter that his work may have fallen, for the moment, into an undeserved obscurity.

THE MISS HILDEGARDE WITHERS SERIES: HILDEGARDE WITHERS MOVIES [source, if different title] (star): STUART PALMER’S SCREEN CREDITS (all in collaboration except those marked *): STUART PALMER BOOKS WITHOUT HILDEGARDE WITHERS:

From Detective Who’s Who (as reprinted in Anthony Boucher’s Four and Twenty Bloodhounds, 1950):

The last word: —Stuart Palmer, “Some of My Best Friends,” Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, June, 1950

|